The Three Trees Architecture

In this article, we’re going to examine a few key concepts in Git that will help you to better understand how it works, and the first of these is the three tree architecture that it uses.

Two-tree architecture

Let’s begin by looking at a typical two-tree architecture. This is what a lot of other version control systems use. We have a repository and a working copy, and those are our two trees.

Now we call them trees because they represent a file structure. All right, our working copy begins with the top of our project directory and below of that might be four or five different folders that have a few files in them, maybe a few more folders, each of those folders has a few more folders in it, and you can imagine that if you map that out, that each of those folders would then branch out like the branches of a tree.

It’s really a directory tree whose trunk begins with the root of our project. Now the repository also has a set of files in it. And when we want to move files between the repository or the working copy, we check out copies–that’s the term that we use–we check it out from the repository into our working directory, and when we finish making our changes we commit those changes back to the repository.

Now the reason why there are two distinct trees is that these files don’t have to be the same between them. If I check out copy from the repository, I make some changes into it, I save those changes on my hard drive.

Now those changes are saved, they are permanent, they are saved in my working copy, but they’re not yet committed to the repository. So my working copy looks different from the repository. Both are saved, it’s not like I haven’t saved the files, I’ve done that. They just aren’t saved and tracked in the version control repository.

Now if the repository is a shared repository, and there are many people working from it, they may commit their changes to the repository. And if I haven’t checked out a copy recently to get those changes, then my working copy doesn’t have their changes.

So once again the repository and the working trees will not have the same information in them. So that’s a typical two-tree architecture.

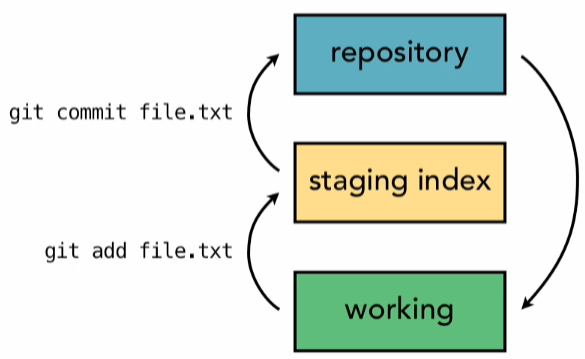

Git however uses a three-tree architecture. It still has the repository and the working copies, but in between is another tree which is the staging index.

We added, then we committed, it was a two-step process.

git add file.txt

git commit file.txt

That add, added our files to the staging index, and then from there we committed to the repository. Now it is possible to go ahead and just commit directly to the repository and skip that staging step.

But it’s important that you understand that this is part of the architecture of Git, and it’s a really nice feature. Because then what it means is that we can make changes to ten different files in our working copy. And then we can say, all right, I am ready to make a commit, but I don’t want to commit all ten of those, I just want to commit five of these as one changed set.

So what I am going to do is I am going to put those on the staging index, add them to the staging index, get those five files ready to go, and as soon as I am satisfied that they are ready, now I will commit those five files in one changed set to the repository. The other five files are still saved in my working tree, but they never got added to the staging index or to the repository. They are sitting there waiting for me to make another commit, to stage those changes and then commit them to the repository.

And of course we can pull things out of the repository in the same way.It’s possible to pull them from the repository to the staging index, from the staging index to the working directory, usually that’s not what we do.

Usually we go ahead and pull them straight from the repository down to the working directory. And in the process the staging index will be updated too. We have our working copy, where we have our changes that we’ve made, and we’ve saved, and saved to our hard drive, but we have not yet committed them to the repository, we haven’t told Git to make this a changed set and to track it.

Then we have the staging index, which is where we prepare things, we stage them for the commit, and then after they’ve been staged, we commit them to the repository so that they are permanently tracked and they now have a commit message attached to them.

References

[1] Jon Leoliger and Matthew McCullogh, Version Control with Git, Second Edition, O’Reilly Media Inc, 2013.