Article Source

[1] Bloom filter, From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Bloom Filter

블룸 필터(Bloom filter)는 원소가 집합에 속하는지 여부를 검사하는데 사용되는 확률적 자료 구조이다. 1970년 Burton Howard Bloom에 의해 고안되었다. 블룸 필터에 의해 어떤 원소가 집합에 속한다고 판단된 경우 실제로는 원소가 집합에 속하지 않는 긍정 오류가 발생하는 것이 가능하지만, 반대로 원소가 집합에 속하지 않는 것으로 판단되었는데 실제로는 원소가 집합에 속하는 부정 오류는 절대로 발생하지 않는다는 특성이 있다. 집합에 원소를 추가하는 것은 가능하나, 집합에서 원소를 삭제하는 것은 불가능하다. 집합 내 원소의 숫자가 증가할수록 긍정 오류 발생 확률도 증가한다.

A Bloom filter is a space-efficient probabilistic data structure, conceived by Burton Howard Bloom in 1970, that is used to test whether an element is a member of a set. False positive matches are possible, but false negatives are not; i.e. a query returns either “possibly in set” or “definitely not in set”. Elements can be added to the set, but not removed (though this can be addressed with a “counting” filter). The more elements that are added to the set, the larger the probability of false positives.

Bloom proposed the technique for applications where the amount of source data would require an impracticably large hash area in memory if “conventional” error-free hashing techniques were applied. He gave the example of a hyphenation algorithm for a dictionary of 500,000 words, out of which 90% follow simple hyphenation rules, but the remaining 10% require expensive disk accesses to retrieve specific hyphenation patterns. With sufficient core memory, an error-free hash could be used to eliminate all unnecessary disk accesses; on the other hand, with limited core memory, Bloom’s technique uses a smaller hash area but still eliminates most unnecessary accesses. For example, a hash area only 15% of the size needed by an ideal error-free hash still eliminates 85% of the disk accesses (Bloom (1970)).

More generally, fewer than 10 bits per element are required for a 1% false positive probability, independent of the size or number of elements in the set (Bonomi et al. (2006)).

Contents

- 1 Algorithm description

- 2 Space and time advantages

- 3 Probability of false positives

- 4 Approximating the number of items in a Bloom filter

- 5 The union and intersection of sets

- 6 Interesting properties

- 7 Examples

- 8 Alternatives

- 9 Extensions and applications

- 10 See also

- 11 Notes

- 12 References

- 13 External links

Algorithm description

An example of a Bloom filter, representing the set {x, y, z}. The colored arrows show the positions in the bit array that each set element is mapped to. The element w is not in the set {x, y, z}, because it hashes to one bit-array position containing 0. For this figure, m=18 and k=3.

An empty Bloom filter is a bit array of m bits, all set to 0. There must also be k different hash functions defined, each of which maps or hashes some set element to one of the m array positions with a uniform random distribution.

To add an element, feed it to each of the k hash functions to get k array positions. Set the bits at all these positions to 1.

To query for an element (test whether it is in the set), feed it to each of the k hash functions to get k array positions. If any of the bits at these positions are 0, the element is definitely not in the set – if it were, then all the bits would have been set to 1 when it was inserted. If all are 1, then either the element is in the set, or the bits have by chance been set to 1 during the insertion of other elements, resulting in a false positive. In a simple Bloom filter, there is no way to distinguish between the two cases, but more advanced techniques can address this problem.

The requirement of designing k different independent hash functions can be prohibitive for large k. For a good hash function with a wide output, there should be little if any correlation between different bit-fields of such a hash, so this type of hash can be used to generate multiple “different” hash functions by slicing its output into multiple bit fields. Alternatively, one can pass k different initial values (such as 0, 1, …, k − 1) to a hash function that takes an initial value; or add (or append) these values to the key. For larger m and/or k, independence among the hash functions can be relaxed with negligible increase in false positive rate (Dillinger & Manolios (2004a), Kirsch & Mitzenmacher (2006)). Specifically, Dillinger & Manolios (2004b) show the effectiveness of deriving the k indices using enhanced double hashing or triple hashing, variants of double hashing that are effectively simple random number generators seeded with the two or three hash values.

Removing an element from this simple Bloom filter is impossible because false negatives are not permitted. An element maps to k bits, and although setting any one of those k bits to zero suffices to remove the element, it also results in removing any other elements that happen to map onto that bit. Since there is no way of determining whether any other elements have been added that affect the bits for an element to be removed, clearing any of the bits would introduce the possibility for false negatives.

One-time removal of an element from a Bloom filter can be simulated by having a second Bloom filter that contains items that have been removed. However, false positives in the second filter become false negatives in the composite filter, which may be undesirable. In this approach re-adding a previously removed item is not possible, as one would have to remove it from the “removed” filter.

It is often the case that all the keys are available but are expensive to enumerate (for example, requiring many disk reads). When the false positive rate gets too high, the filter can be regenerated; this should be a relatively rare event.

Space and time advantages

Bloom filter used to speed up answers in a key-value storage system. Values are stored on a disk which has slow access times. Bloom filter decisions are much faster. However some unnecessary disk accesses are made when the filter reports a positive (in order to weed out the false positives). Overall answer speed is better with the Bloom filter than without the Bloom filter. Use of a Bloom filter for this purpose, however, does increase memory usage.

While risking false positives, Bloom filters have a strong space advantage over other data structures for representing sets, such as self-balancing binary search trees, tries, hash tables, or simple arrays or linked lists of the entries. Most of these require storing at least the data items themselves, which can require anywhere from a small number of bits, for small integers, to an arbitrary number of bits, such as for strings (tries are an exception, since they can share storage between elements with equal prefixes). Linked structures incur an additional linear space overhead for pointers. A Bloom filter with 1% error and an optimal value of k, in contrast, requires only about 9.6 bits per element — regardless of the size of the elements. This advantage comes partly from its compactness, inherited from arrays, and partly from its probabilistic nature. The 1% false-positive rate can be reduced by a factor of ten by adding only about 4.8 bits per element.

However, if the number of potential values is small and many of them can be in the set, the Bloom filter is easily surpassed by the deterministic bit array, which requires only one bit for each potential element. Note also that hash tables gain a space and time advantage if they begin ignoring collisions and store only whether each bucket contains an entry; in this case, they have effectively become Bloom filters with k = 1.[1]

Bloom filters also have the unusual property that the time needed either to add items or to check whether an item is in the set is a fixed constant, O(k), completely independent of the number of items already in the set. No other constant-space set data structure has this property, but the average access time of sparse hash tables can make them faster in practice than some Bloom filters. In a hardware implementation, however, the Bloom filter shines because its k lookups are independent and can be parallelized.

To understand its space efficiency, it is instructive to compare the general Bloom filter with its special case when k = 1. If k = 1, then in order to keep the false positive rate sufficiently low, a small fraction of bits should be set, which means the array must be very large and contain long runs of zeros. The information content of the array relative to its size is low. The generalized Bloom filter (k greater than 1) allows many more bits to be set while still maintaining a low false positive rate; if the parameters (k and m) are chosen well, about half of the bits will be set, and these will be apparently random, minimizing redundancy and maximizing information content.

Probability of false positives

The false positive probability

as a function of number of elements

as a function of number of elements

in the filter and the filter size

in the filter and the filter size

.

An optimal number of hash functions

.

An optimal number of hash functions  has been assumed.

has been assumed.

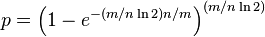

Assume that a hash function selects each array position with equal probability. If m is the number of bits in the array, and k is the number of hash functions, then the probability that a certain bit is not set to 1 by a certain hash function during the insertion of an element is then

The probability that it is not set to 1 by any of the hash functions is

If we have inserted n elements, the probability that a certain bit is still 0 is

the probability that it is 1 is therefore

Now test membership of an element that is not in the set. Each of the k array positions computed by the hash functions is 1 with a probability as above. The probability of all of them being 1, which would cause the algorithm to erroneously claim that the element is in the set, is often given as

![\left(1-\left[1-\frac{1}{m}\right]{kn}\right)\k \approx

\left( 1-e{-kn/m}

\right)\k.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/2/1/8/2180ac79da81e5b3721963b4d80cf5a6.png)

This is not strictly correct as it assumes independence for the probabilities of each bit being set. However, assuming it is a close approximation we have that the probability of false positives decreases as m (the number of bits in the array) increases, and increases as n (the number of inserted elements) increases.

An alternative analysis arriving at the same approximation without the

assumption of independence is given by Mitzenmacher and

Upfal.[2] After all n items have been added to the

Bloom filter, let q be the fraction of the m bits that are set to 0.

(That is, the number of bits still set to 0 is qm.) Then, when testing

membership of an element not in the set, for the array position given by

any of the k hash functions, the probability that the bit is found set

to 1 is

.

So the probability that all k hash functions find their bit set to 1

is

.

So the probability that all k hash functions find their bit set to 1

is  .

Further, the expected value of q is the probability that a given array

position is left untouched by each of the k hash functions for each of

the n items, which is (as above)

.

Further, the expected value of q is the probability that a given array

position is left untouched by each of the k hash functions for each of

the n items, which is (as above)

![E[q] = \left(1 -

\frac{1}{m}\right){kn}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/2/7/d/27d8109a8f8463478c6d3922dc6c0428.png) .

.

It is possible to prove, without the independence assumption, that q is very strongly concentrated around its expected value. In particular, from the Azuma–Hoeffding inequality, they prove that[3]

![\Pr(\left|q - E[q]\right| \ge \frac{\lambda}{m}) \le

2\exp(-2\lambda\2/m)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/b/2/2/b220b6db28cc2b3d0c35b08b92060fd8.png)

Because of this, we can say that the exact probability of false positives is

![\sum_{t} \Pr(q = t) (1 - t)\k \approx (1 - E[q])\k =

\left(1-\left[1-\frac{1}{m}\right]{kn}\right)\k \approx \left(

1-e{-kn/m}

\right)\k](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/b/0/9/b09ba941c93c7d94f8d62d0772af6dac.png)

as before.

a> Optimal number of hash functions —

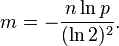

For a given m and n, the value of k (the number of hash functions) that minimizes the probability is

which gives

The required number of bits m, given n (the number of inserted elements) and a desired false positive probability p (and assuming the optimal value of k is used) can be computed by substituting the optimal value of k in the probability expression above:

which can be simplified to:

This results in:

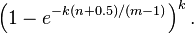

This means that for a given false positive probability p, the length of a Bloom filter m is proportionate to the number of elements being filtered n.[4] While the above formula is asymptotic (i.e. applicable as m,n → ∞), the agreement with finite values of m,n is also quite good; the false positive probability for a finite bloom filter with m bits, n elements, and k hash functions is at most

So we can use the asymptotic formula if we pay a penalty for at most half an extra element and at most one fewer bit.[5]

Approximating the number of items in a Bloom filter

Swamidass & Baldi (2007) showed that the number of items in a Bloom filter can be approximated with the following formula,

![X\* = - \tfrac{ N \ln \left[ 1 - \tfrac{X}{N} \right] } { k}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/7/0/a/70a20610ea03d5789d9b29248a63b9b7.png)

where

is an estimate of the number of items in the filter, N is length of the

filter, k is the number of hash functions per item, and X is the number

of bits set to one.

is an estimate of the number of items in the filter, N is length of the

filter, k is the number of hash functions per item, and X is the number

of bits set to one.

The union and intersection of sets

Bloom filters are a way of compactly representing a set of items. It is

common to try and compute the size of the intersection or union between

two sets. Bloom filters can be used to approximate the size of the

intersection and union of two sets. Swamidass & Baldi

(2007) showed that for two bloom filters of

length

,

their counts, respectively can be estimated as

,

their counts, respectively can be estimated as

![A\* = -N \ln \left[ 1 - A / N \right] /

k](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/f/b/6/fb65666b660f0ebb95d08833aff41d25.png)

and

![B\* = -N \ln \left[ 1 - B / N

\right]/k](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/0/e/6/0e654f20c67c166e428cb80790270758.png) .

.

The size of their union can be estimated as

![A\*\cup B\* = -N \ln \left[ 1 - A \cup B / N

\right]/k](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/c/8/e/c8e13a05eed128a21a6c7f9141d5aa13.png) ,

,

where  is the number of bits set to one in either of the two bloom filters. And

the intersection can be estimated as

is the number of bits set to one in either of the two bloom filters. And

the intersection can be estimated as

,

,

Using the three formulas together.

Interesting properties

-

Unlike a standard hash table, a Bloom filter of a fixed size can represent a set with an arbitrary large number of elements; adding an element never fails due to the data structure “filling up.” However, the false positive rate increases steadily as elements are added until all bits in the filter are set to 1, at which point all queries yield a positive result.

-

Union and intersection of Bloom filters with the same size and set of hash functions can be implemented with bitwise OR and AND operations, respectively. The union operation on Bloom filters is lossless in the sense that the resulting Bloom filter is the same as the Bloom filter created from scratch using the union of the two sets. The intersect operation satisfies a weaker property: the false positive probability in the resulting Bloom filter is at most the false-positive probability in one of the constituent Bloom filters, but may be larger than the false positive probability in the Bloom filter created from scratch using the intersection of the two sets.

-

Some kinds of superimposed code can be seen as a Bloom filter implemented with physical edge-notched cards. An example is Zatocoding, invented by Calvin Mooers in 1947, in which the set of categories associated with a piece of information is represented by notches on a card, with a random pattern of four notches for each category.

Examples

Google BigTable and Apache Cassandra use Bloom filters to reduce the disk lookups for non-existent rows or columns. Avoiding costly disk lookups considerably increases the performance of a database query operation.[6]

The Google Chrome web browser uses a Bloom filter to identify malicious URLs. Any URL is first checked against a local Bloom filter and only upon a hit a full check of the URL is performed.[7]

The Squid Web Proxy Cache uses Bloom filters for cache digests.[8]

Bitcoin uses Bloom filters to verify payments without running a full network node.[9][10]

The Venti archival storage system uses Bloom filters to detect previously stored data.[11]

The SPIN model checker uses Bloom filters to track the reachable state space for large verification problems.[12]

The Cascading analytics framework uses Bloom filters to speed up asymmetric joins, where one of the joined data sets is significantly larger than the other (often called Bloom join[13] in the database literature).[14]

Alternatives

Classic Bloom filters use

bits of space per inserted key, where

bits of space per inserted key, where

is the false positive rate of the Bloom filter. However, the space that

is strictly necessary for any data structure playing the same role as a

Bloom filter is only

is the false positive rate of the Bloom filter. However, the space that

is strictly necessary for any data structure playing the same role as a

Bloom filter is only

per key (Pagh, Pagh & Rao 2005). Hence Bloom

filters use 44% more space than a hypothetical equivalent optimal data

structure. The number of hash functions used to achieve a given false

positive rate

per key (Pagh, Pagh & Rao 2005). Hence Bloom

filters use 44% more space than a hypothetical equivalent optimal data

structure. The number of hash functions used to achieve a given false

positive rate

is proportional to

is proportional to

which is not optimal as it has been proved that an optimal data

structure would need only a constant number of hash functions

independent of the false positive rate.

which is not optimal as it has been proved that an optimal data

structure would need only a constant number of hash functions

independent of the false positive rate.

Stern & Dill (1996) describe a probabilistic structure based on hash tables, hash compaction, which Dillinger & Manolios (2004b) identify as significantly more accurate than a Bloom filter when each is configured optimally. Dillinger and Manolios, however, point out that the reasonable accuracy of any given Bloom filter over a wide range of numbers of additions makes it attractive for probabilistic enumeration of state spaces of unknown size. Hash compaction is, therefore, attractive when the number of additions can be predicted accurately; however, despite being very fast in software, hash compaction is poorly suited for hardware because of worst-case linear access time.

Putze, Sanders & Singler (2007) have studied some variants of Bloom filters that are either faster or use less space than classic Bloom filters. The basic idea of the fast variant is to locate the k hash values associated with each key into one or two blocks having the same size as processor’s memory cache blocks (usually 64 bytes). This will presumably improve performance by reducing the number of potential memory cache misses. The proposed variants have however the drawback of using about 32% more space than classic Bloom filters.

The space efficient variant relies on using a single hash function that

generates for each key a value in the range

![\left[0,n/\varepsilon\right]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/8/7/1/8719561052ee96a6f1c88ae38a05dbe2.png) where

where

is the requested false positive rate. The sequence of values is then

sorted and compressed using Golomb

coding (or some other compression

technique) to occupy a space close to

is the requested false positive rate. The sequence of values is then

sorted and compressed using Golomb

coding (or some other compression

technique) to occupy a space close to

bits. To query the Bloom filter for a given key, it will suffice to

check if its corresponding value is stored in the Bloom filter.

Decompressing the whole Bloom filter for each query would make this

variant totally unusable. To overcome this problem the sequence of

values is divided into small blocks of equal size that are compressed

separately. At query time only half a block will need to be decompressed

on average. Because of decompression overhead, this variant may be

slower than classic Bloom filters but this may be compensated by the

fact that a single hash function need to be computed.

bits. To query the Bloom filter for a given key, it will suffice to

check if its corresponding value is stored in the Bloom filter.

Decompressing the whole Bloom filter for each query would make this

variant totally unusable. To overcome this problem the sequence of

values is divided into small blocks of equal size that are compressed

separately. At query time only half a block will need to be decompressed

on average. Because of decompression overhead, this variant may be

slower than classic Bloom filters but this may be compensated by the

fact that a single hash function need to be computed.

Another alternative to classic Bloom filter is the one based on space efficient variants of cuckoo hashing. In this case once the hash table is constructed, the keys stored in the hash table are replaced with short signatures of the keys. Those signatures are strings of bits computed using a hash function applied on the keys.

Extensions and applications

Counting filters

Counting filters provide a way to implement a delete operation on a Bloom filter without recreating the filter afresh. In a counting filter the array positions (buckets) are extended from being a single bit to being an n-bit counter. In fact, regular Bloom filters can be considered as counting filters with a bucket size of one bit. Counting filters were introduced by Fan et al. (1998).

The insert operation is extended to increment the value of the buckets and the lookup operation checks that each of the required buckets is non-zero. The delete operation, obviously, then consists of decrementing the value of each of the respective buckets.

Arithmetic overflow of the buckets is a problem and the buckets should be sufficiently large to make this case rare. If it does occur then the increment and decrement operations must leave the bucket set to the maximum possible value in order to retain the properties of a Bloom filter.

The size of counters is usually 3 or 4 bits. Hence counting Bloom filters use 3 to 4 times more space than static Bloom filters. In theory, an optimal data structure equivalent to a counting Bloom filter should not use more space than a static Bloom filter.

Another issue with counting filters is limited scalability. Because the counting Bloom filter table cannot be expanded, the maximal number of keys to be stored simultaneously in the filter must be known in advance. Once the designed capacity of the table is exceeded, the false positive rate will grow rapidly as more keys are inserted.

Bonomi et al. (2006) introduced a data structure based on d-left hashing that is functionally equivalent but uses approximately half as much space as counting Bloom filters. The scalability issue does not occur in this data structure. Once the designed capacity is exceeded, the keys could be reinserted in a new hash table of double size.

The space efficient variant by Putze, Sanders & Singler (2007) could also be used to implement counting filters by supporting insertions and deletions.

Rottenstreich, Kanizo & Keslassy (2012) introduced a new general method based on variable increments that significantly improves the false positive probability of counting Bloom filters and their variants, while still supporting deletions. Unlike counting Bloom filters, at each element insertion, the hashed counters are incremented by a hashed variable increment instead of a unit increment. To query an element, the exact values of the counters are considered and not just their positiveness. If a sum represented by a counter value cannot be composed of the corresponding variable increment for the queried element, a negative answer can be returned to the query.

Data synchronization

Bloom filters can be used for approximate data synchronization as in Byers et al. (2004). Counting Bloom filters can be used to approximate the number of differences between two sets and this approach is described in Agarwal & Trachtenberg (2006).

Bloomier filters

Chazelle et al. (2004) designed a generalization of Bloom filters that could associate a value with each element that had been inserted, implementing an associative array. Like Bloom filters, these structures achieve a small space overhead by accepting a small probability of false positives. In the case of “Bloomier filters”, a false positive is defined as returning a result when the key is not in the map. The map will never return the wrong value for a key that is in the map.

Compact approximators

Boldi & Vigna (2005) proposed a lattice-based generalization of Bloom filters. A compact approximator associates to each key an element of a lattice (the standard Bloom filters being the case of the Boolean two-element lattice). Instead of a bit array, they have an array of lattice elements. When adding a new association between a key and an element of the lattice, they compute the maximum of the current contents of the k array locations associated to the key with the lattice element. When reading the value associated to a key, they compute the minimum of the values found in the k locations associated to the key. The resulting value approximates from above the original value.

Stable Bloom filters

Deng & Rafiei (2006) proposed Stable Bloom filters as a variant of Bloom filters for streaming data. The idea is that since there is no way to store the entire history of a stream (which can be infinite), Stable Bloom filters continuously evict stale information to make room for more recent elements. Since stale information is evicted, the Stable Bloom filter introduces false negatives, which do not appear in traditional bloom filters. The authors show that a tight upper bound of false positive rates is guaranteed, and the method is superior to standard bloom filters in terms of false positive rates and time efficiency when a small space and an acceptable false positive rate are given.

Scalable Bloom filters

Almeida et al. (2007) proposed a variant of Bloom filters that can adapt dynamically to the number of elements stored, while assuring a minimum false positive probability. The technique is based on sequences of standard bloom filters with increasing capacity and tighter false positive probabilities, so as to ensure that a maximum false positive probability can be set beforehand, regardless of the number of elements to be inserted.

Attenuated Bloom filters

An attenuated bloom filter of depth D can be viewed as an array of D normal bloom filters. In the context of service discovery in a network, each node stores regular and attenuated bloom filters locally. The regular or local bloom filter indicates which services are offered by the node itself. The attenuated filter of level i indicates which services can be found on nodes that are i-hops away from the current node. The i-th value is constructed by taking a union of local bloom filters for nodes i-hops away from the node.[15]

Attenuated Bloom Filter Example

Let’s take a small network shown on the graph below as an example. Say we are searching for a service A whose id hashes to bits 0,1, and 3 (pattern 11010). Let n1 node to be the starting point. First, we check whether service A is offered by n1 by checking its local filter. Since the patterns don’t match, we check the attenuated bloom filter in order to determine which node should be the next hop. We see that n2 doesn’t offer service A but lies on the path to nodes that do. Hence, we move to n2 and repeat the same procedure. We quickly find that n3 offers the service, and hence the destination is located.[16]

By using attenuated Bloom filters consisting of multiple layers, services at more than one hop distance can be discovered while avoiding saturation of the Bloom filter by attenuating (shifting out) bits set by sources further away.[15]

Chemical structure searching

Bloom filters are commonly used to search large databases of chemicals (see chemical similarity). Each molecule is represented with a bloom filter (called a fingerprint in this field) which stores substructures of the molecule. Commonly, the tanimoto similarity is used to quantify the similarity between molecules’ bloom filters.

See also

Notes

- [](#cite_ref-1) Mitzenmacher & Upfal (2005).

- [](#cite_ref-2) Mitzenmacher & Upfal (2005), pp. 109–111, 308.

- [](#cite_ref-3) Mitzenmacher & Upfal (2005), p. 308.

- [](#cite_ref-4) Starobinski, Trachtenberg & Agarwal (2003).

- [](#cite_ref-5) Goel & Gupta (2010).

- [](#cite_ref-6) (Chang et al. 2006).

- [](#cite_ref-7) http://blog.alexyakunin.com/2010/03/nice-bloom-filter-application.html

- [](#cite_ref-Wessels172_8-0) Wessels, Duane (January 2004), “10.7 Cache Digests”, Squid: The Definitive Guide (1st ed.), O’Reilly Media, p. 172, ISBN 0-596-00162-2, “Cache Digests are based on a technique first published by Pei Cao, called Summary Cache. The fundamental idea is to use a Bloom filter to represent the cache contents.”

- [](#cite_ref-9) Bitcoin 0.8.0

- [](#cite_ref-10) Core Development Status Report #1

- [](#cite_ref-11) http://plan9.bell-labs.com/magic/man2html/8/venti

- [](#cite_ref-12) http://spinroot.com/

- [](#cite_ref-13) Mullin (1990)

- [](#cite_ref-14) http://blog.liveramp.com/2013/04/03/bloomjoin-bloomfilter-cogroup/

- \ a b Koucheryavy et al. (2009)

- [](#cite_ref-16) Kubiatowicz et al. (2000)

References

- Koucheryavy, Y.; Giambene, G.; Staehle, D.; Barcelo-Arroyo, F.; Braun, T.; Siris, V. (2009), “Traffic and QoS Management in Wireless Multimedia Networks”, COST 290 Final Report (USA): 111

- Kubiatowicz, J.; Bindel, D.; Czerwinski, Y.; Geels, S.; Eaton, D.;

Gummadi, R.; Rhea, S.; Weatherspoon, H. et al. (2000), “Oceanstore:

An architecture for global-scale persistent

storage”,

ACM SIGPLAN Notices (USA): 190–201

|displayauthors=suggested (help) - Agarwal, Sachin; Trachtenberg, Ari (2006), “Approximating the number of differences between remote sets”, IEEE Information Theory Workshop (Punta del Este, Uruguay): 217, doi:10.1109/ITW.2006.1633815, ISBN 1-4244-0035-X

- Ahmadi, Mahmood; Wong, Stephan (2007), “A Cache Architecture for Counting Bloom Filters”, 15th international Conference on Networks (ICON-2007), p. 218, doi:10.1109/ICON.2007.4444089, ISBN 978-1-4244-1229-7

- Almeida, Paulo; Baquero, Carlos; Preguica, Nuno; Hutchison, David (2007), “Scalable Bloom Filters”, Information Processing Letters 101 (6): 255–261, doi:10.1016/j.ipl.2006.10.007

- Byers, John W.; Considine, Jeffrey; Mitzenmacher, Michael; Rost, Stanislav (2004), “Informed content delivery across adaptive overlay networks”, IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking 12 (5): 767, doi:10.1109/TNET.2004.836103

- Bloom, Burton H. (1970), “Space/Time Trade-offs in Hash Coding with Allowable Errors”, Communications of the ACM 13 (7): 422–426, doi:10.1145/362686.362692

- Boldi, Paolo; Vigna, Sebastiano (2005), “Mutable strings in Java: design, implementation and lightweight text-search algorithms”, Science of Computer Programming 54 (1): 3–23, doi:10.1016/j.scico.2004.05.003

- Bonomi, Flavio; Mitzenmacher, Michael; Panigrahy, Rina; Singh, Sushil; Varghese, George (2006), “An Improved Construction for Counting Bloom Filters”, Algorithms – ESA 2006, 14th Annual European Symposium, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 4168, pp. 684–695, doi:10.1007/11841036_61, ISBN 978-3-540-38875-3

- Broder, Andrei; Mitzenmacher, Michael (2005), “Network Applications of Bloom Filters: A Survey”, Internet Mathematics 1 (4): 485–509, doi:10.1080/15427951.2004.10129096

- Chang, Fay; Dean, Jeffrey; Ghemawat, Sanjay; Hsieh, Wilson; Wallach, Deborah; Burrows, Mike; Chandra, Tushar; Fikes, Andrew; Gruber, Robert (2006), “Bigtable: A Distributed Storage System for Structured Data”, Seventh Symposium on Operating System Design and Implementation

- Charles, Denis; Chellapilla, Kumar (2008), “Bloomier Filters: A second look”, The Computing Research Repository (CoRR), arXiv:0807.0928

- Chazelle, Bernard; Kilian, Joe; Rubinfeld, Ronitt; Tal, Ayellet (2004), “The Bloomier filter: an efficient data structure for static support lookup tables”, Proceedings of the Fifteenth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, pp. 30–39

- Cohen, Saar; Matias, Yossi (2003), “Spectral Bloom Filters”, Proceedings of the 2003 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, pp. 241–252, doi:10.1145/872757.872787, ISBN 158113634X [dead\ link]

- Deng, Fan; Rafiei, Davood (2006), “Approximately Detecting Duplicates for Streaming Data using Stable Bloom Filters”, Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD Conference, pp. 25–36

- Dharmapurikar, Sarang; Song, Haoyu; Turner, Jonathan; Lockwood, John (2006), “Fast packet classification using Bloom filters”, Proceedings of the 2006 ACM/IEEE Symposium on Architecture for Networking and Communications Systems, pp. 61–70, doi:10.1145/1185347.1185356, ISBN 1595935800

- Dietzfelbinger, Martin; Pagh, Rasmus (2008), “Succinct Data Structures for Retrieval and Approximate Membership”, The Computing Research Repository (CoRR), arXiv:0803.3693

- Swamidass, S. Joshua; Baldi, Pierre (2007), “Mathematical correction for fingerprint similarity measures to improve chemical retrieval”, Journal of chemical information and modeling (ACS Publications) 47 (3): 952–964, PMID 17444629

- Dillinger, Peter C.; Manolios, Panagiotis (2004a), “Fast and Accurate Bitstate Verification for SPIN”, Proceedings of the 11th International Spin Workshop on Model Checking Software, Springer-Verlag, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 2989

- Dillinger, Peter C.; Manolios, Panagiotis (2004b), “Bloom Filters in Probabilistic Verification”, Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Formal Methods in Computer-Aided Design, Springer-Verlag, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 3312

- Donnet, Benoit; Baynat, Bruno; Friedman, Timur (2006), “Retouched Bloom Filters: Allowing Networked Applications to Flexibly Trade Off False Positives Against False Negatives”, CoNEXT 06 – 2nd Conference on Future Networking Technologies

- Eppstein, David; Goodrich, Michael T. (2007), “Space-efficient straggler identification in round-trip data streams via Newton’s identities and invertible Bloom filters”, Algorithms and Data Structures, 10th International Workshop, WADS 2007, Springer-Verlag, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 4619, pp. 637–648, arXiv:0704.3313

- Fan, Li; Cao, Pei; Almeida, Jussara; Broder, Andrei (2000), “Summary Cache: A Scalable Wide-Area Web Cache Sharing Protocol”, IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking 8 (3): 281–293, doi:10.1109/90.851975 . A preliminary version appeared at SIGCOMM ‘98.

- Goel, Ashish; Gupta, Pankaj (2010), “Small subset queries and bloom filters using ternary associative memories, with applications”, ACM Sigmetrics 2010 38: 143, doi:10.1145/1811099.1811056

- Kirsch, Adam; Mitzenmacher, Michael (2006), “Less Hashing, Same Performance: Building a Better Bloom Filter”, in Azar, Yossi; Erlebach, Thomas, Algorithms – ESA 2006, 14th Annual European Symposium, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 4168, Springer-Verlag, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 4168, pp. 456–467, doi:10.1007/11841036, ISBN 978-3-540-38875-3

- Mortensen, Christian Worm; Pagh, Rasmus; Pătraşcu, Mihai (2005), “On dynamic range reporting in one dimension”, Proceedings of the Thirty-seventh Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, pp. 104–111, doi:10.1145/1060590.1060606, ISBN 1581139608

- Pagh, Anna; Pagh, Rasmus; Rao, S. Srinivasa (2005), “An optimal Bloom filter replacement”, Proceedings of the Sixteenth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, pp. 823–829

- Porat, Ely (2008), “An Optimal Bloom Filter Replacement Based on Matrix Solving”, The Computing Research Repository (CoRR), arXiv:0804.1845

- Putze, F.; Sanders, P.; Singler, J. (2007), “Cache-, Hash- and Space-Efficient Bloom Filters”, in Demetrescu, Camil, Experimental Algorithms, 6th International Workshop, WEA 2007, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 4525, Springer-Verlag, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 4525, pp. 108–121, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-72845-0, ISBN 978-3-540-72844-3

- Sethumadhavan, Simha; Desikan, Rajagopalan; Burger, Doug; Moore, Charles R.; Keckler, Stephen W. (2003), “Scalable hardware memory disambiguation for high ILP processors”, 36th Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture, 2003, MICRO-36, pp. 399–410, doi:10.1109/MICRO.2003.1253244, ISBN 0-7695-2043-X

- Shanmugasundaram, Kulesh; Brönnimann, Hervé; Memon, Nasir (2004), “Payload attribution via hierarchical Bloom filters”, Proceedings of the 11th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, pp. 31–41, doi:10.1145/1030083.1030089, ISBN 1581139616

- Starobinski, David; Trachtenberg, Ari; Agarwal, Sachin (2003), “Efficient PDA Synchronization”, IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2 (1): 40, doi:10.1109/TMC.2003.1195150

- Stern, Ulrich; Dill, David L. (1996), “A New Scheme for Memory-Efficient Probabilistic Verification”, Proceedings of Formal Description Techniques for Distributed Systems and Communication Protocols, and Protocol Specification, Testing, and Verification: IFIP TC6/WG6.1 Joint International Conference, Chapman & Hall, IFIP Conference Proceedings, pp. 333–348, CiteSeerX: 10.1.1.47.4101

- Haghighat, Mohammad Hashem; Tavakoli, Mehdi; Kharrazi, Mehdi (2013), “Payload Attribution via Character Dependent Multi-Bloom Filters”, Transaction on Information Forensics and Security, IEEE 99 (5): 705, doi:10.1109/TIFS.2013.2252341

- Mitzenmacher, Michael; Upfal, Eli (2005), Probability and computing: Randomized algorithms and probabilistic analysis, Cambridge University Press, pp. 107–112, ISBN 9780521835404

- Mullin, James K. (1990), “Optimal semijoins for distributed database systems”, Software Engineering, IEEE Transactions on 16 (5): 558–560

- Rottenstreich, Ori; Kanizo, Yossi; Keslassy, Isaac (2012), “The Variable-Increment Counting Bloom Filter”, 31st Annual IEEE International Conference on Computer Communications, 2012, Infocom 2012, pp. 1880–1888, doi:10.1109/INFCOM.2012.6195563, ISBN 978-1-4673-0773-4

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bloom filter.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bloom filter.

- Why Bloom filters work the way they do (Michael Nielsen, 2012)

- Table of false-positive rates for different configurations from a University of Wisconsin–Madison website

- Interactive Processing demonstration from ashcan.org

- “More Optimal Bloom Filters,” Ely Porat (Nov/2007) Google TechTalk video on YouTube

- “Using Bloom Filters” Detailed Bloom Filter explanation using Perl

- “A Garden Variety of Bloom

Filters

- Explanation and Analysis of Bloom filter variants

Implementations

This article’s use of external links may not follow Wikipedia’s policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links, and converting useful links where appropriate into footnote references. (April 2013)

This article’s use of external links may not follow Wikipedia’s policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links, and converting useful links where appropriate into footnote references. (April 2013)

- Implementation in C from literateprograms.org

- Implementation in C++11 on github.com

- Implementation in C# from codeplex.com

- Implementation in Erlang from sites.google.com

- Implementation in Haskell from haskell.org

- Implementation in Java on github.com

- Implementation in Javascript from la.ma.la

- Implementation in JS for node.js on github.com

- Implementation in Lisp from lemonodor.com

- Implementation in Perl from CPAN

- Implementation in PHP from code.google.com

- Implementation in Python, Traditional Bloom Filter from pypi.python.org

- Implementation in Python, Scalable Bloom Filter from pypi.python.org

- Implementation in Ruby from rubyinside.com

- Implementation in Scala from codecommit.com

- Implementation in Tcl from kocjan.org

- Implementation in TypeScript from codeplex.com