Article Source

- Title: The Forgotten History Of CGI

- Authors: Ron Miller

The Forgotten History Of CGI

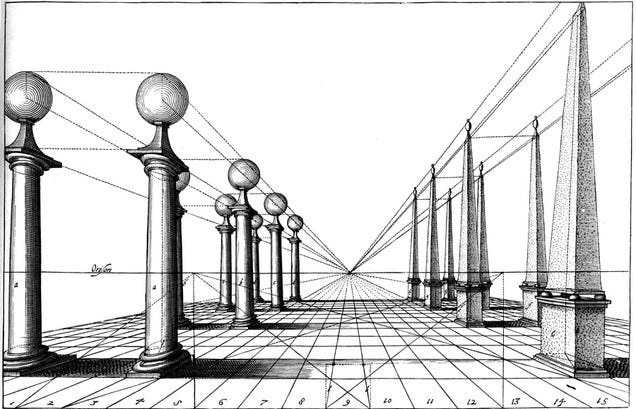

The roots of CGI lie in the first mechanical aids to drawing and painting. The earliest of these were developed to help solve a problem every artist has found to be sticky: perspective.

Before the introduction of geometric perspective, the realistic depiction of nature was not one of the purposes of art. Instead, artists chose the size and position of objects in a picture by their relative importance to one another. A distant castle might appear to be larger than one in the foreground simply because it was considered more important.

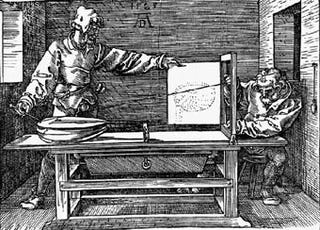

Italian artist Filippo Brunelleschi (1377—1446) created the rules of perspective in the early fifteenth century. His breakthroughs led artists to portray the world as it really looked to the human eye. Some artists, such as Albrecht Durer (1471—1528) of Germany, even went so far as to make special tools to help them create mathematically perfect perspective drawings. These were perhaps the first mechanical devices to be used to create art.

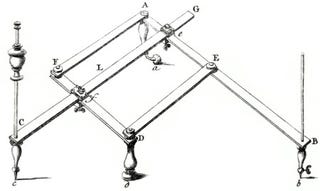

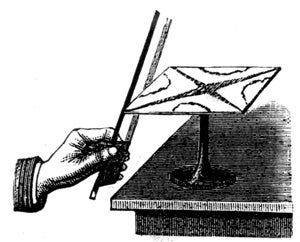

Most artists quickly adapted these new technologies to create their artwork. In the ensuing centuries they have used all sorts of machines to make the creation of art easier. The pantograph, for instance, is a simple mechanical device that enlarges or reduces a drawing. Pantographs are not only still used by artists today, they have wide applications in modern industry as well.

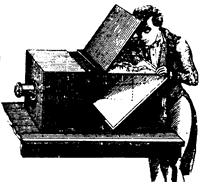

Artists also use a camera obscura ( “dark room” in Latin). The earliest of these were full-size, light-tight rooms with a small hole in an outside wall. Visitors would see an image of the surrounding landscape projected onto the opposite wall. Artists used this concept in a different way. They reduced the room to a small box with a tiny pinhole in one side and a white screen opposite to it. When the light from a scene or model passes through the pinhole, an image is projected onto the screen. The artist can then easily trace the image. It’s still a valuable tool used by many artists today (who usually shorten the name to “lucy”).

The camera lucida eventually evolved into what we know today as just…

The Camera

Occasionally, an innovation is not met with such widespread enthusiasm. After the invention of photography in the early nineteenth century, painter Paul Delaroche said that photography “completely satisfies art’s every need.” By this he meant that a photograph could do anything an artist could, so painters would become useless.

Delaroche reflected the feelings of many academic painters, who supported themselves by making highly lifelike paintings: portraits, landscapes, historical scenes, and so forth that pleased their rich patrons. The camera could capture scenes with an accuracy that even the finest painter could not achieve. Photography was also cheap and could be done by anyone.

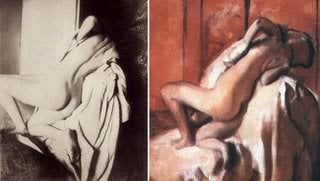

Many artists, though, quickly realized the possibilities of photography, looking at it not as a rival but as an ally. For example, Eugene Delacroix (1798—1863) studied the human body by using photographs of the nude. He also worked from photographs of models when making drawings and paintings.

Many other artists began doing this too since photos were much easier than living models, who not only might move while posing but also charged for their time. (Eadweard Muybridge made this into a science, in the process laying the foundation for motion pictures…but that’s another story.)

Meanwhile, other artists found it advantageous to let photography take over the dull depiction of reality. It freed them to explore other realms of color, light, and composition. Impressionism and other schools of art that sprang up at the end of the nineteenth century might have been delayed by decades, if not longer, if not for the liberating influence of photography.

The airbrush was another transformative mechanical innovation. Invented in 1879 by Abner Peeler, the airbrush uses compressed air to create a jet of very fine paint particles. By adjusting the amount of air pressure and the amount of paint, artists can create soft lines and shapes and blend colors together smoothly. The airbrush also creates incredible lighting effects. Although a very valuable tool, the airbrush has taken a great deal of abuse. Traditional painters often consider it a form of cheating.

Many professional artists dislike that non-artists can easily create beautiful effects with an airbrush. Unfortunately, the result is often beautiful effects but very bad art. Airbrush art soon became associated— unfairly perhaps—with cheap, gaudy, amateur artwork. Although it quickly became one of the most important tools of modern artists working in advertising and illustration, most other artists scorned it.

Mathematics and Art

Scientists have long exploited the connection between the visual and the numerical. They have used machines and other devices to translate numerical data into visual form for more than a century.

For instance, in 1787 the German physicist Ernst Chladni found that when he drew a violin bow against the edge of a metal plate covered with fine sand,complex patterns would form in the sand. Depending on where the plate was stroked by the bow, he could create different patterns. The practical application of Chladni’s discovery has been in the design of musical instruments. But the patterns in themselves are pleasing and are perhaps one of the earliest examples of machine-generated art.

The oscilloscope—which detects electrical pulses and translates them into waves on a screen—is probably the very earliest electronic machine developed to translate numerical data to visual form. German scientist Karl Ferdinand Braun developed the first oscilloscope in 1897. The basic technology of Braun’s invention included the cathode-ray tube—which eventually became the television tube.

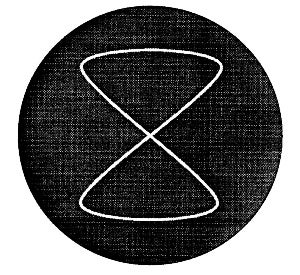

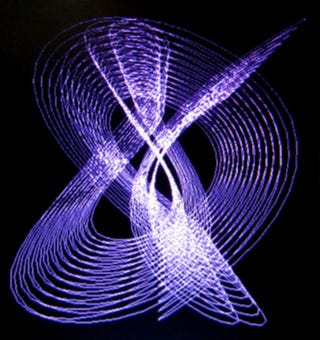

Naturally, some creative minds saw the potential for art in the oscilloscope’s perfectly shaped waves. Since an oscilloscope could create special wave shapes by changing the data input to the device, gifted artists could produce spectacular waves of complex lines. But the only way to save an oscilloscope image was to take a photograph of the oscilloscope screen.

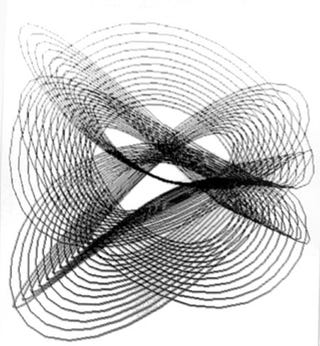

Two devices create patterns like oscilloscopes through purely mechanical means. The harmonograph was a very popular household item in the late nineteenth century. It used the principle of the pendulum to make complex patterns of swirling lines. The simplest harmonograph uses a pendulum swinging over an area of smooth sand. As the pendulum swings, a point on the end traces out patterns in the sand. Mathematicians call these patterns Lissajous figures.

In other versions, the pendulum’s bob consisted of a large cone (such as a paper cup) filled with fine sand. The sand drained from a small hole in its point. Very complex patterns resulted when several pendulum actions were combined, such as when one pendulum swung from another. A harmonograph that creates really complex patterns can be quite large—though still simple to build.

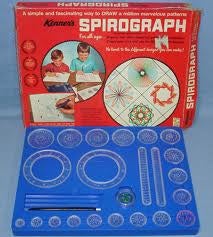

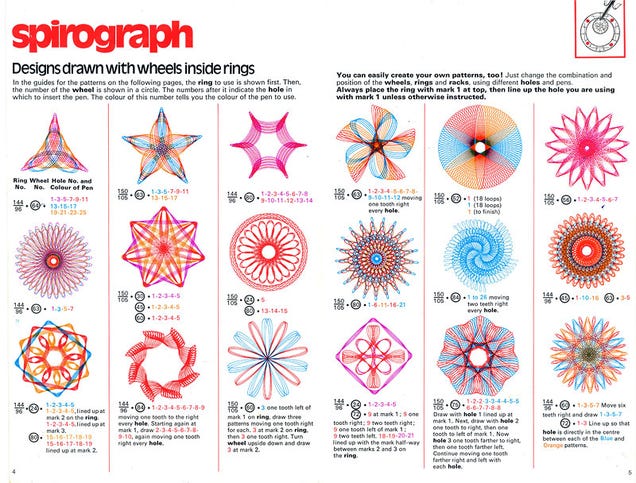

In 1966 the Kenner toy company introduced the Spirograph in the United States. The simple toy has several geared plastic wheels and toothed rings that can create beautiful curves. The toy is based on a type of mathematical curve called a trochoid. A trochoid is the path of a point fixed relative to a circle that is rolling along a straight line.

Imagine a reflector attached to one of the spokes of a bicycle wheel. When the wheel turns, the reflector makes a circle as it rotates around the hub. But if the bicycle is moving relative to the ground, the reflector follows a curve that looks like a series of arcs. Imagine the cyclist was part of a circus act and drove her bike around the inside of a large curved track. Then the reflector would trace out an even more complex curve called an epicycloid. If more circles are added, the curves become even more complex.

The Computer

The early computers of the late 1940s and 1950s output data through typewriter-like devices. This was usually in the form of columns of numbers and letters. Artist realized these letters and numbers could be seen as areas of light and dark. For instance, an mor xlooks darker on the page than an o, i,or dot. Pictures could be created if users fed the right numbers into the computer.

By using combinations of many different characters, users could create complex and surprisingly realistic images. The process was very similar to the way black-and-white photos are reproduced in newspapers, magazines, and books. The photo is broken up into tiny dots. The size of the dot determines how dark it is. Small dots have a lot of white around them and look lighter, while larger dots make a space look darker.

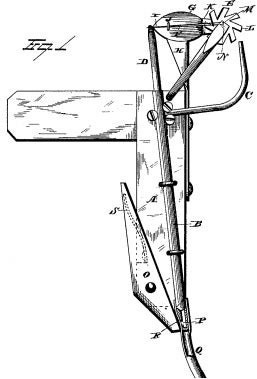

A plotter is another device that creates images with the computer. It is a pen that the computer moves over a sheet of paper in two directions: up and down and back and forth. By combining these two motions, users can make the computer draw complex curves. Plotters can produce very detailed work, as well as work of very large dimensions. People soon realized that computers could be used to make curves and graphs that were visually appealing. Thus, the computer might be a tool for creating art.

The First Computer Art

The first tools used to make electronic art—a predecessor to digital art— were originally designed for testing sound equipment. The company that eventually became Hewlett Packard developed the first of these products, an audio oscillator. This instrument creates one pure tone, or frequency, at a time. The waves that this tone produces can be displayed on the screen of an oscilloscope. The patterns on the oscilloscope screen give scientists and engineers information about the wave and its source.

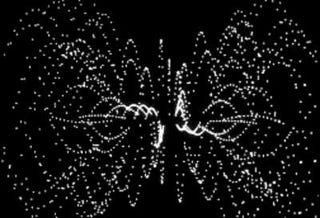

Ben Laposky, an artist and mathematician from Cherokee, Iowa, realized that by changing the input he could create patterns of his own design. In 1950 he created the first graphic images made by an electronic machine. Laposky captured his electronic oscilloscope imagery by photographing it onto high-speed film. He called them oscillons and electronic abstractions.

Meanwhile, the Viennese artist Herbert W. Franke also created electronic images. Franke’s images were similar to those of Laposky’s but reflected his own artistic sensibilities and goals. Franke eventually wrote the first book on digital art: Computer**Graphics-Computer Art(1971).

John Whitney Sr., who studied music and photography, closely followed Laposky’s and Franke’s work. In the 1940s, Whitney created an experimental film with his brother James that won first prize at a film festival in Belgium. His work in 1955 as a director of animation at the famous UPA cartoon studios led him to a partnership with Saul Bass. Together they created the title sequence for the Alfred Hitchcock film Vertigo(1958), as well as graphics for television shows.

In 1960 Whitney founded Motion Graphics Incorporated. The company used a computer to produce motion picture and television sequences and commercials. Whitney had built the computer himself from war-surplus electronics. Gradually it evolved into a huge machine that towered 12 feet (3.6 meters) high. Whitney continued to perfect his computer and the effects it created.

In 1961 Whitney produced a seven-minute color film called Catalog.In this film, he showed all the effects he had perfected with his homemade computer. Whitney achieved worldwide recognition for his work with the analog computer. In 1966 IBM awarded him the company’s first artist-in-residence status, allowing him to freely explore the potential of computer graphics.

The First Digital Artists

By the mid-1960s, some artists began to explore ways to combine computer technology with art. Until then artistical experiments with computers had been more or less limited to engineers. Only they had the technical expertise to use computers. The interactive software that is so readily available in modern times didn’t exist. Programs had to be created from scratch, custom built for each individual computer.

Also, computers were not readily available. Until the 1970s, computers were enormous and very expensive. For instance, Sketchpad was the first program specifically designed to create drawings.

Ivan Sutherland developed the program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1963 on one of the most advanced computers of the time. The machine itself occupied 1,000 square feet (93 sq. m) of space. It had a main memory of 320 kilobytes—that is, about 320,000 units of information—stored in a memory core about 1 cubic yard (0.8 cu. m) in size. Users fed the computer programs on a punched paper tape while the drawings appeared on a 7-inch (18-centimeter) black-and-white monitor. By comparison, a modern desktop computer that costs only a few hundred dollars may have up to 200 gigabytes of memory. That’s 200 billion units, more than a quarter million times that of the computer used by Sketchpad!

In spite of these drawbacks, many artists and scientists became successful partners in the creation of the first computer-aided artwork. But this collaboration was long in coming. Scientists held the first exhibitions of computer art in 1965 and featured only work created by scientists. Two years later, however, artists Billy Kluver and Robert Rauschenberg founded an organization called Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT).The organization, funded in part by Bell Laboratories (later Luminent), tried to bridge the gap between artists and scientists. A number of important avant-garde artists, including Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and composer John Cage, contributed work.

The work of these very famous artists could be found in major museums and galleries all around the world. Not surprisingly, these particular artists embraced the new technology. Most of them had already been using new technologies in creating their art, so the move to digital art was probably both easy and natural. Rauschenberg, for instance, created elaborate montages with the help of photographic techniques. Warhol employed the halftone processes used in creating photos in newspapers and magazines. And John Cage had long been interested in electronic music. The interest in digital art from these respected artists gave the form a kind of official seal of approval. People who once scorned the use of computers in creating art became interested in it.

In 1968 Jasia Reichardt created a two-month-long exhibition called Cybernetic Serendipity at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, England. It included work by 325 artists and scientists from around the world, including important work by John Cage, John Whitney Sr., Charles Csuri, Michael Noll, and many others. After closing in London, the exhibition went to Washington, D.C., and San Francisco, California. While not the first such exhibition, it was one of the largest. It made the art world and the general public fully aware of computer and electronic art.

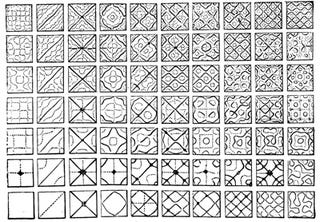

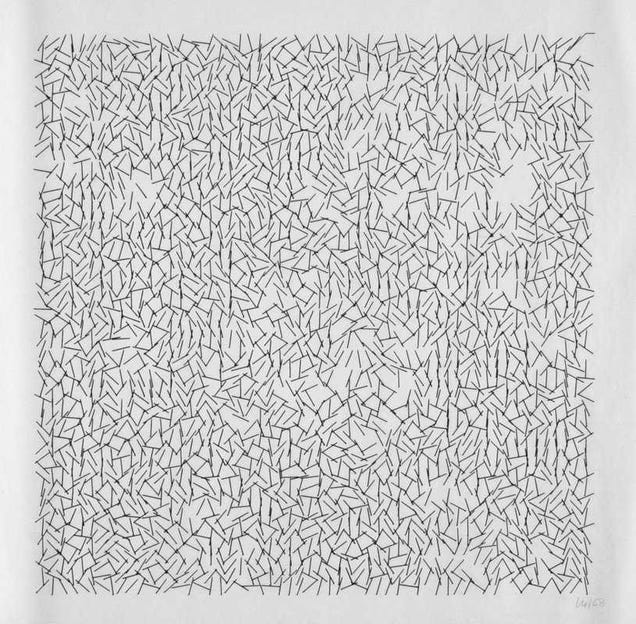

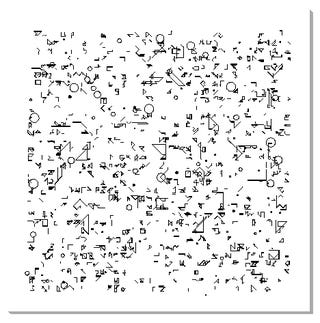

In 1968 Hungarian artist Vera Molnar began using the computer to transform basic geometric shapes, such as squares, circles, and triangles. She rotated them, deformed them, erased parts, or combined different shapes into new ones. Then she printed her final results with a plotter.

“Proceeding by small steps,” she said, “the painter is in a position to delicately pinpoint the image of dreams. Without the aid of a computer, it would not be possible to materialize quite so faithfully an image that previously existed only in the artist’s mind. This may sound paradoxical, but the machine, which is thought to be cold and inhuman, can help to realize what is most subjective, unattainable, and profound in a human being.”

In 1969 German artist Manfred Mohr turned from traditional painting to the computer. He worked on variations of the cube, which he distorted and transformed endlessly. Mohr worked only in black and white, using a plotter to print his work. In 1971 the Musee d’Art Moderne de laVille de Paris gave him a one-man show. It was the first such honor from any museum for a computer artist.

Larry Cuba is a widely known pioneer of computer animation. He created his first film, First Fig,in 1974. Computers capable of digital art were not easy to come by at that time. So Cuba joined with computer scientists at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. In 1975 John Whitney Sr. invited Cuba to work with him on the movie Arabesque.Later films, such as 3/78 (Objects and Transformations)(1978), Two Space(1979), and Calculated**Movements(1985) have been shown all over the world.

Lillian Schwartz pioneered the use of computers in graphics, film, video, animation, special effects, virtual reality, and multimedia. Her work was the first in the new medium of computer-aided art to be bought by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The museum used her sculpture, Proxima Centauri,in its 1968 Machine Exhibition.

Independently and in collaboration with scientists at Bell Labs, Schwartz later developed ways to use computers in film and animation. Her award-winning films—such as Mirage(1974)—have been shown all over the world.

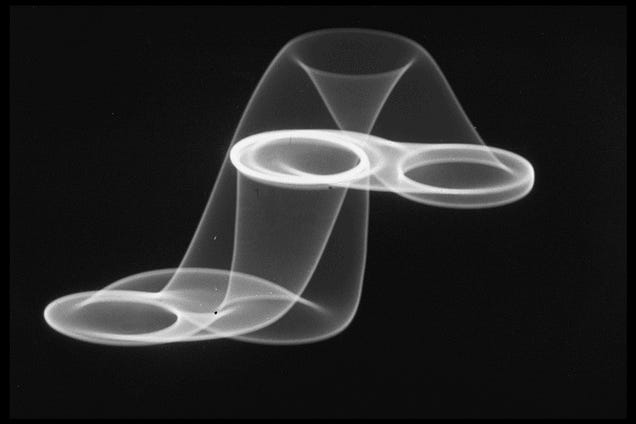

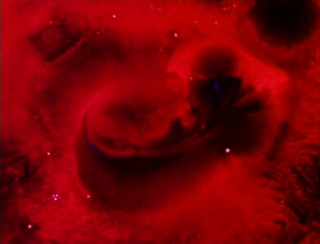

Yoichiro Kawaguchi, one of the leading international computer artists, originally teamed up with computer scientists. With their help, he developed art using metaballs. This technology, invented by Jim Blinn, created soft, fluid, organic shapes. Before this, most computer artists were limited to hard-edged geometric shapes. The patterns Kawaguchi found in natural forms, such as seashells and plants, inspired him. He won many international honors and awards for his art and animation.

Ed Emshwiller is mostly famed as a science-fiction illustrator. He was also a highly respected video artist and dean of the School of Film/Video at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia. He helped influence the experimental film movement in the 1960s. Many of his films, including Thanatopsis(1962), Totem(1963), Relativity(1966), and Three Dancers(1970), received awards and screenings at film festivals in cities around the world. He was quick to embrace digital technology in the creation of films like Sunstone (1979).

In 1987 Emshwiller created Hungers,an electronic video opera, for the Los Angeles Arts Festival. Hungerscombined live performance and interactive devices that changed the sound of the music according to the environment. No two performances were exactly alike.

Fractals

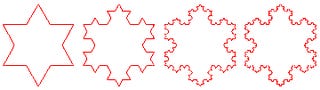

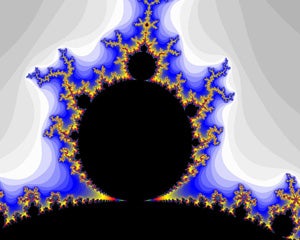

Another major advance in digital art occurred when mathematicians discovered fractals. While fractals involve complex math, the basic concept is simple.

Start with an equilateral triangle. Divide one side of the triangle into three equal parts, and remove the middle section. Replace it with two lines the same length as the section you just removed. Do this to all three sides of the triangle.

The result will be a six-pointed star. Do this again with the twelve new sides you’ve created. And do it again and again . . . The resulting figure is called a Koch snowflake, after the Swedish mathematician Helge von Koch, who first described it in 1904.

Fractals are special because they look the same at any scale. A close-up of any detail of a fractal looks just like a larger section. You can zoom in as much as you like, and the fractal will always look the same. Fractals can be found throughout nature. A branch of a tree, for instance, looks like the entire tree. A rock looks like the mountain it was found on. The indentations of a coastline seen from space look like the indentations of a coastline seen from only a few feet away or even when seen under a magnifying glass.

For more than half a century, mathematicians working on complex fractals rarely knew what they might actually look like. Mathematicians were only able to make rough sketches by hand, so it wasn’t possible to make out their true intricacy. When mathematicians first plotted fractals with computers in the late 1960s, they finally discovered their amazing beauty—and artists quickly realized their potential.

In the mid-1970s, Mandelbrot introduced what he called fractal geometry. With the aid of computer graphics, Mandelbrot showed how his math formulas could describe complex, irregular natural forms. Examples of these are the formation of clouds, the distribution of leaves and twigs on a tree, the shape of a coastline, or the spiraling form of a seashell. To do this, he had to develop not only new math concepts but also had to develop some of the first computer programs capable of printing graphics.

By this time, many artists realized the potential of the computer as a tool. But the widespread use and development of digital art had to wait until technicians created software that would work on any computer. Also, small, less expensive computers had to become widely available. This did not occur on a wide scale until the 1980s. And we all know what happened after that.

Illustration sources:

Digital Art, Ron Miller (21st Century Books, 2008)

Yoichiro Kawaguchi: http://www.cs.otago.ac.nz/graphite/guest…

Lillian Schwartz: http://thesoundofeye.blogspot.com/2010/04/direct…

Manfred Mohr: http://digitalartmuseum.org

Vera Molnar: http://digitalartmuseum.org

Herbert Franke: http://dam.org/artists/phase-one/herbert-w-franke