Article Source

- Title: Transfer Learning — part 2

Transfer Learning — Part II

Zero/one/few-shot learning

It is easy to train models when data is abundant. Oftentimes, it is not the case and one can have just a few examples to learn from. An extreme form of transfer learning can help here.

Imagine training a classifier that learns to discriminate between dogs and wolfs and all the dogs in the training set are shepherd dogs. Now, you want to classify an image of chihuahua. If you have a few labeled chihuahua images, you can try to use them to adapt your model. This is few-shot learning problem. Your case can get worse. Imagine having just one example (one-shot learning) or even no labeled chihuahua at all (zero-shot learning). It can get even worse if someone will try to use your dog/wolf classifier to classify a truck. Can you adapt your model to classify his truck?

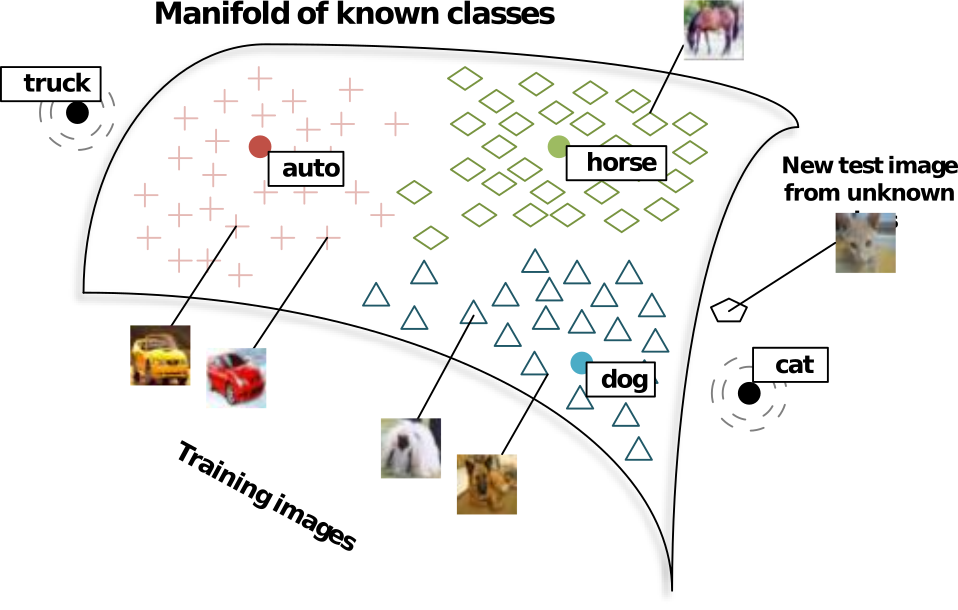

At the first glance, the worst case of few-shot/zero-shot learning seems almost unsolvable. However, there is a solution. Think of k-nearest neighbors (kNN). If we had a representation of the data that extracts the most pertinent features of the input and makes it easy to separate classes, we can map a new unlabeled example to this representation and use kNN to determine labels. You can tell me: but, wait, aren’t you limited to the labeling that you have in your training data? and, what if all the nearest neighbors are not really near? You are right. It is not yet zero-shot learning, but this scheme can work for few-shot learning. After observing a few examples of the new class, you can hope to learn to recognize the new class with kNN. This, of course, can go wrong if you learned your feature mapping only on shepherd dog / wolf images and chihuahua-related features were eliminated from the representation.

Zero-shot learning

Imagine now that we have a good mapping given to us and the space where it maps the inputs has all its points labeled. In this case, kNN-based approach will work. The problem here is to construct such a labeled space and mapping from the feature space to this space.

We can take a more general approach to finding a good representation. We can construct a vector-space embedding for both labels and training examples so that a training example and its label are mapped as close to each other as possible in such a common space.

This approach is actively used in image classification: a common space embedding is learned for images and for words and words serve as labels. Wouldn’t it be great if we had a vector space embedding of multiple labels that reflects semantic relationships between word-labels so that word-labels “dog”, “cat”, and “mammal” are closer to each other than to “table” whereas “table” is closer to “chair” than to “cat”? We would have been able to map a new image to this space and then take the label of the nearest neighbor even if it is not in the set of training images. Luckily, it is possible to learn such word embeddings in an unsupervised fashion from large collections of textual data, see word2vec (Mikolov et al. 2013), fastText (Bojanowski et al. 2017), GloVe (Pennington, Socher, and Manning 2014), or recent Poincare embeddings (Nickel and Kiela 2017). Using labeled data, one can learn embeddings of images of dogs/wolfs to the word embedding space, so that images of dogs are mapped to the neighborhood of the “dog” word-vector. When a new example is given, it is mapped to embedding space and closest word-vector (nearest neighbor) is taken as a predicted label for this example.

Socher et al. (2013) used pretrained embeddings trained on Wikipedia texts and they learned neural network based mapping of images to word-embedding vector space.

Taken from Socher et al. (2013) Norouzi et al. (2013) proposed a very simple method to embed images into a pretrained word-vector embedding space. Having trained a multi-class image classifier, they used predicted probabilities of classes to perform probability-weighted average of the word-embedding vectors corresponding to labels of the classes.

Romera-Paredes and Torr (2015) developed a linear transformation based approach to zero-shot learning that however requires a characterization of labels and training examples in terms of attributes. They then learn matrices that when combined with attribute-vectors give a linear mapping to common space. This is similar to other methods, but more restrictive as the mapping to common space is not learned from the data end-to-end, but requires side-information for training.

For the comparison of different approaches to zero-shot learning, please see Xian et al. (2018).

Few-shot learning

Few-shot learning is related to the field of Meta-Learning (learning how to learn) where a model is required to quickly learn a new task from a small amount of new data.

Lake et al. (2011) proposed an approach to one-shot learning inspired by human learning of simple visual concepts — handwritten characters. In their model, a handwritten character is a noisy combination of strokes that people use during drawing. They proposed a generative model that learns a library of strokes and combines the strokes from this library to generate characters. Given a new character for one-shot learning and a candidate character for evaluation, both characters modeled as a superposition of strokes, Lake et al. (2011) estimated the probability that the candidate character is composed of the same strokes as the new character and these strokes are mixed in a similar way.

What about Deep Learning? First, let me go back to our kNN example. What allows kNN to achieve few-shot learning? It is the memory. A new training example is memorized, and then, when a similar new testing example arrives, kNN searches its memory for similar examples and finds the memorized training example and its label. Standard Deep Learning architectures, however, do not allow for rapid assimilation (memorization) of the new data and instead require extensive training.

To solve this problem, one can combine kNN with data representations obtained with Deep Learning (Deep Learning + kNN based memory). Alternatively, one can try to augment Deep Neural Networks with memory in a more direct way that allows for end-to-end training.

Koch, Zemel, and Salakhutdinov (2015) developed few-shot learning method based on nearest neighbour classification with similarity metric learned by a Siamese neural network. Siamese neural networks were developed in 90s (Bromley et al. 1994) for learning a similarity metric between two inputs. Siamese network consists of two identical subnetworks (shared weights) joined at their outputs. Each subnetwork receives its own input, and the output of the whole network determines the similarity between the two inputs. After Koch, Zemel, and Salakhutdinov (2015) learned the metric, simple nearest neighbour classifier was used.

Santoro et al. (2016) developed a few-shot learning method using Memory-Augmented Neural Network (MANN). The idea of their model was similar to Neural Turing Machines (Graves, Wayne, and Danihelka 2014): a neural network extended with an external memory module so that the model is differentiable and can be trained end-to-end. Thanks to their training procedure, they forced the network to learn general knowledge whereas the quick memory access allowed to rapidly bind this general knowledge to new data.

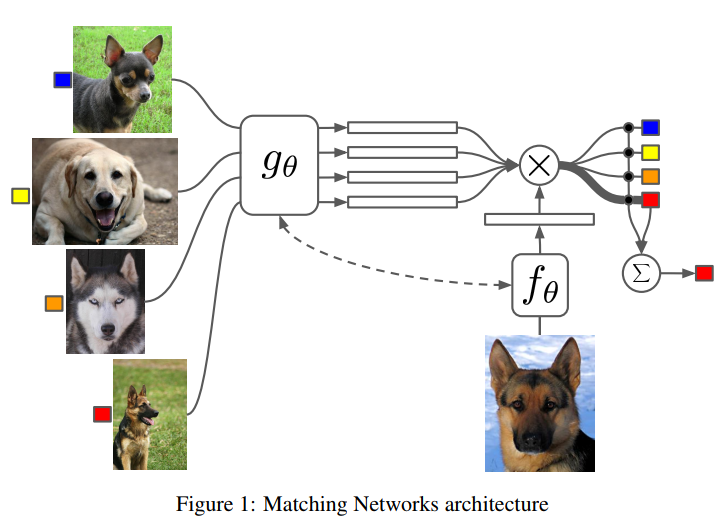

Vinyals et al. (2016) proposed a neural network model that implements an end-to-end training procedure that combines feature extraction and differentiable kNN with cosine similarity. They used one network to embed a small set of labeled images (support set) and another network to embed an unlabelled image to the same space. Then they computed the softmax transformation of cosine similarities computed between every embedded image in support set and the embedded unlabeled image. This was used as an approximation of the probability distribution over labels from the support set. They then proposed an improvement when the whole support set (context) was used to embed every example in the support set as well as unlabeled test example (they used LSTM to achieve this).

Taken from Vinyals et al. (2016) Ravi and Larochelle (2016) proposed to modify gradient-based optimization to allow for few-shot learning. In a general view of gradient-based optimization, at every step of an optimization algorithm, an optimizer (say SGD) uses gradient information to propose the next parameters based on their previous values. Ravi and Larochelle (2016) replaced SGD update rule (linear with respect to gradient) by a nonlinear function of the history of parameter updates, current empirical risk, and its gradient. Specifically, they used Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network (Hochreiter and Schmidhuber 1997) to learn an nonlinear update rule for training a neural network.

In their Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning algorithm (MAML) paper, Finn, Abbeel, and Levine (2017) proposed few-shot learning method that is applicable to any model that can be trained with gradient descent. To cite the authors: “In effect, we will aim to find model parameters that are sensitive to changes in the task, such that small changes in the parameters will produce large improvements on the loss function of any task drawn from the distribution of tasks when altered in the direction of the gradient of that loss”. The goal is to learn one model for all tasks so that its internal representations are well suited to all tasks (transferable). To achieve this, first, a general model is trained for a one or more gradient descent steps on a single task on a few training examples. This produces a model that is slightly more adapted to a particular task, a task-specific model. Second, task-specific model is used to evaluate cumulative loss on some set of other tasks. This multi-task loss is then used to perform meta-optimization step: to update the parameters of the general model with gradient descent.

Taken from Wu et al. (2018) Wu et al. (2018) proposed Meta-learning autoencoder for few-shot prediction (MeLA). The model consists of meta-recognition model that takes features and labels of new data as inputs and returns a latent code. This code is used as an input to meta-generative model that generates parameters of a task-specific model. That is the task-specific model is not trained by gradient descent, but generated from a few examples corresponding to a task. Moreover, the generated model can be improved with a few gradient steps. The capability to generate a model from few examples corresponding to a task can be interpreted as an interpolation in the space of models. In order for it to be successful, tasks used for training MeLA should be sufficiently similar.

That is all for today. Thanks for reading. Please follow us in order not to miss our next post on multi-domain / multi-task transfer learning.

References

Bojanowski, Piotr, Edouard Grave, Armand Joulin, and Tomas Mikolov.

- “Enriching Word Vectors with Subword Information.” Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 5: 135–46.

Bromley, Jane, Isabelle Guyon, Yann LeCun, Eduard Säckinger, and Roopak Shah. 1994. “Signature Verification Using a” Siamese” Time Delay Neural Network.” In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 737–44.

Finn, Chelsea, Pieter Abbeel, and Sergey Levine. 2017. “Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning for Fast Adaptation of Deep Networks.” In ICML.

Graves, Alex, Greg Wayne, and Ivo Danihelka. 2014. “Neural Turing Machines.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1410.5401.

Hochreiter, Sepp, and Jürgen Schmidhuber. 1997. “Long Short-Term Memory.” Neural Computation 9 (8): 1735–80.

Koch, Gregory, Richard Zemel, and Ruslan Salakhutdinov. 2015. “Siamese Neural Networks for One-Shot Image Recognition.” In ICML Deep Learning Workshop. Vol. 2.

Lake, Brenden, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, Jason Gross, and Joshua Tenenbaum.

- “One Shot Learning of Simple Visual Concepts.” In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society. Vol. 33.

Mikolov, Tomas, Ilya Sutskever, Kai Chen, Greg S Corrado, and Jeff Dean.

- “Distributed Representations of Words and Phrases and Their Compositionality.” In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 3111–9.

Nickel, Maximilian, and Douwe Kiela. 2017. “Poincaré Embeddings for Learning Hierarchical Representations.” In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30, edited by I. Guyon, U. V. Luxburg, S. Bengio, H. Wallach, R. Fergus, S. Vishwanathan, and R. Garnett, 6341–50. Curran Associates, Inc. http://papers.nips.cc/paper/7213-poincare-embeddings-for-learning-hierarchical-representations.pdf.

Norouzi, Mohammad, Tomas Mikolov, Samy Bengio, Yoram Singer, Jonathon Shlens, Andrea Frome, Gregory S. Corrado, and Jeffrey Dean. 2013. “Zero-Shot Learning by Convex Combination of Semantic Embeddings.” CoRR abs/1312.5650.

Pennington, Jeffrey, Richard Socher, and Christopher Manning. 2014. “Glove: Global Vectors for Word Representation.” In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 1532–43.

Ravi, Sachin, and Hugo Larochelle. 2016. “Optimization as a Model for Few-Shot Learning.” In.

Romera-Paredes, Bernardino, and Philip Torr. 2015. “An Embarrassingly Simple Approach to Zero-Shot Learning.” In International Conference on Machine Learning, 2152–61.

Santoro, Adam, Sergey Bartunov, Matthew Botvinick, Daan Wierstra, and Timothy P. Lillicrap. 2016. “Meta-Learning with Memory-Augmented Neural Networks.” In ICML.

Socher, Richard, Milind Ganjoo, Christopher D Manning, and Andrew Ng.

- “Zero-Shot Learning Through Cross-Modal Transfer.” In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 935–43.

Vinyals, Oriol, Charles Blundell, Timothy P. Lillicrap, Koray Kavukcuoglu, and Daan Wierstra. 2016. “Matching Networks for One Shot Learning.” In NIPS.

Wu, Tailin, John Peurifoy, Isaac L Chuang, and Max Tegmark. 2018. “Meta-Learning Autoencoders for Few-Shot Prediction.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1807.09912.

Xian, Yongqin, Christoph H. Lampert, Bernt Schiele, and Zeynep Akata.

- “Zero-Shot Learning — A Comprehensive Evaluation of the Good, the Bad and the Ugly.” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence.